Vulva lichen sclerosus and lichen planus

This information is about two particular skin conditions, lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, which can affect different parts of the body but which more commonly affect the vulva. These conditions may occasionally develop into vulval cancer after many years. Only a small number of women with lichen sclerosus or lichen planus (around 3–5%) will develop cancer.

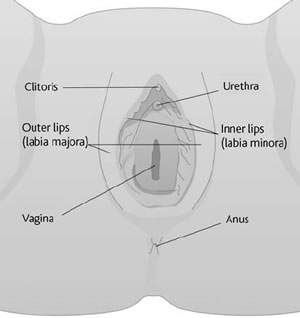

The vulva

The vulva is a woman’s external genital area. It includes two large, hair-covered folds of skin called the labia majora, which surround two thin and delicate folds called the labia minora. The labia majora and labia minora surround the opening of the vagina (birth canal) and the urethra (the tube through which urine is passed). The clitoris is positioned above the vagina and urethra: this small structure is very sensitive and helps a woman to reach sexual climax (orgasm). The anus (opening to the back passage) is separated from the vulva by an area of skin called the perineum.

Vulval lichen sclerosus (LS) and lichen planus (LP)

LS and LP are fairly common, non-cancerous skin conditions that can occur in the skin on any part of the body. They can affect children as well as adults. These changes are not cancer, but in a few people they may, over many years, develop into a type of skin cancer known as squamous cell cancer.

In vulval LS and LP, changes occur in the skin of the vulva. It is a slowly developing inflammation of the skin in the vulval area that can be controlled by treatment but cannot be cured.

Causes

The causes are not known, but some women with these conditions have other family members with LS or LP, so it is thought that the changes may sometimes be caused by an inherited faulty gene. They are more common in older women, and in women who have auto-immune illnesses such as thyroid problems or pernicious anaemia. It is not possible to get LS or LP through sexual intercourse: they are not sexually transmitted diseases and they are not infectious.

Signs and symptoms

The skin in the affected areas is very itchy and sore, with an abnormal appearance and a change in colour. The skin becomes more fragile than normal skin and may split, causing stinging and pain. The vulva may become distorted, causing a change in the shape or size. Occasionally this leads to difficulties with passing urine or having sexual intercourse. The vagina may become narrowed, and sexual intercourse may become uncomfortable.

The symptoms vary from woman to woman and some women with these conditions have no symptoms at all. In this case the conditions may be discovered during medical examinations for other health problems.

The above symptoms can be caused by conditions other than LP or LS. If you have any of these symptoms, let your doctor know. Your doctor can then examine you and refer you to a doctor who specialises in women’s health (a gynaecologist).

How it is diagnosed

As the signs and symptoms of LS and LP can vary and are similar to other conditions of the vulva, it is necessary to take a small sample of cells from the affected area to examine them under a microscope. This is known as a biopsy and is done in the outpatient department. An anaesthetic cream is usually used to numb the vulval area before the biopsy is taken and it takes 20 minutes to work. Local anaesthetic is then injected into the area, using a small needle. Sometimes a general anaesthetic may be given. A sample of cells (about the size of a peppercorn) is then taken from the vulva, using a biopsy tool.

Treatment

Often no treatment will be needed, but if you have severe LS or LP you will need to see your doctor regularly. If the symptoms, such as itching or soreness, begin to become troublesome, it can help to use a non-perfumed moisturiser instead of soap in the vulval area. A type of steroid ointment (clobetasol proprionate, called Dermovate®) can be prescribed by your doctor and is often used twice a day for three months. After this your doctor may recommend you to use the cream twice a week. This treatment is safe, can often control the symptoms very well, and can help women to go back to a normal life. However, it will not get rid of the condition completely. The treatment can make the skin more supple and so can help to make intercourse easier.

Surgery is rarely used to treat LS or LP. Sometimes it may be used to relieve the problems that scarring can cause, such as a narrowed vaginal opening, which can make sexual intercourse difficult and painful.

Follow-up

As lichen sclerosus or lichen planus are long-term conditions that cannot be completely cured, you will be seen by your specialist regularly, as you may continue to have symptoms. Women who have had either of these conditions for many years have a small risk of developing a vulval cancer. This usually occurs in women in their 60s–90s rather than in younger women. It is important to see your doctor or nurse regularly to check for any signs of a cancer developing, so that treatment can be given at an early stage, when there is a high chance of cure.

Your feelings

Many women feel frightened when they are first told that they have lichen sclerosus or lichen planus, and worry that they may develop cancer. You may find the treatments embarrassing and frightening, and may feel tense, tearful, or withdrawn. At times these feelings can be overwhelming and hard to control. Everyone has their own way of coping with difficult situations. Some people find it helpful to talk to friends or family, while others prefer to seek help from people outside their situation. Others may prefer to keep their feelings to themselves. There is no right or wrong way to cope, but help is available if you need it.

References

This section has been compiled using information from a number of reliable sources including:

- Oxford Textbook of Oncology (2nd edition). Souhami et al. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Cancer and Its Management (4th edition). Souhami and Tobias. Oxford Blackwell Scientific Publications, 2003.

- Principles & Practice of Gynaecologic Oncology (3rd edition). Hoskins et al. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000.

For further references, please see the general bibliography.

Page last modified: 02 November 2005

- Q&As