Chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis

This information is about myelofibrosis which is one of a group of conditions known as the chronic myeloproliferative diseases (CMPDs).

The chronic myeloproliferative diseases

The myeloproliferative (pronounced mi low pro liff er a tiv) diseases are a group of conditions affecting the function of the bone marrow. They involve an over-production of one or more of the blood cells that are produced in the bone marrow. The conditions are related to cancer and rarely they may develop into a form of leukaemia.

The main types of chronic myeloproliferative disease are:

- essential thrombocythaemia (throm bo si theme ia)

- polycythaemia vera (polly si theme ia)

- idiopathic myelofibrosis (my low fi bro sis)

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) is also a myeloproliferative disease although it is usually dealt with as a separate condition.

The bone marrow

This is the spongy material in the centre of some of our bones. It produces cells known as stem cells. These are immature cells that develop into three different types of blood cells:

- Red blood cells carry oxygen to all cells in the body.

- White blood cells fight infections and form part of our immune system.

- Platelets help the blood to clot, to prevent bleeding.

Chronic idiopathic myelofibrosis

Idiopathic myelofibrosis is a condition in which scar tissue (fibrosis) develops in the bone marrow (myelo). The word idiopathic means the cause is not known. MF can develop because the bone marrow has been producing too many platelets (due to essential thrombocythaemia) or too many red blood cells (due to polycythaemia vera). It can also develop without any history of these other myeloproliferative diseases.

There are other conditions that can cause the bone marrow to become scarred and these are treated differently. Various tests and investigations will be done to determine the exact cause.

As the bone marrow becomes more scarred (fibrosed) it is less able to produce enough blood cells. To help compensate for this, the liver and the spleen begin to produce blood cells, and as a result these organs become enlarged. The liver and spleen are not as efficient at making blood cells as the bone marrow, which can lead to low levels of blood cells in the body. When the spleen becomes enlarged it can ‘hold on’ to the blood cells and is involved in their destruction.

Myelofibrosis is a rare condition that mainly affects people over 50 years of age. The causes of this condition are unknown.

Signs and symptoms

Myelofibrosis may not cause any symptoms initially and some people are diagnosed after they have had a routine blood test for another reason, when they have no symptoms.

As the bone marrow becomes less able to produce enough blood cells the following symptoms may occur:

- feeling very tired, even breathless at the slightest effort, because of a lack of red blood cells

- bruising without any injury, or unusual bleeding, such as nose bleeds, bleeding gums or a very heavy menstrual period because of a low number of platelets

- repeated infections because of a lack of white blood cells

- pain and discomfort because the spleen is enlarged

- fevers and night sweats

- kidney stones

- unexplained weight loss

Diagnosis

Myelofibrosis is usually diagnosed by a haematologist (a specialist in blood disorders). Diagnosis is often made following a simple blood test called a full blood count. This counts the number of the red cells, white cells and platelets in the blood.

Other conditions can cause the bone marrow to become fibrosed. These need to be ruled out before a diagnosis of myelofibrosis can be made.

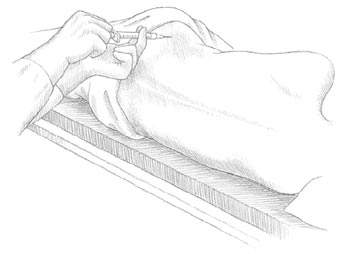

Bone-marrow aspirate Samples of bone marrow are usually taken to look for fibrous tissue. This involves taking a sample of bone marrow from the back of the hipbone (pelvis) or occasionally the breast bone (sternum) using a needle (a bone marrow aspirate).

The bone-marrow sample is taken under a local anaesthetic. You are given a small injection to numb the area and a needle is passed gently through the skin into the bone. A tiny sample of the marrow is then drawn (aspirated) into a syringe.

Trephine biopsy It can often be difficult to get a sample, because the bone marrow is very scarred. This is known as a ‘dry tap’. If this occurs you will probably need to have a core of the bone marrow taken (a trephine biopsy). This will usually be taken from the hipbone and takes a few minutes longer. A trephine biopsy can be painful for a few seconds and you may feel some discomfort for a few hours afterwards. You may need to take some mild painkillers, like paracetemol.

If a diagnosis of myelofibrosis is suspected but the bone marrow samples are apparently normal, your doctor may want to repeat them with samples taken from a different part of the body. This is because in the early stages of the disease not all the bone marrow may be affected.

Other tests and investigations may also be done, such as scans and x-rays. Your doctor or nurse will explain these to you.

Treatment

Treatment of myelofibrosis aims to control symptoms without causing too many side effects, and will depend on how the disease is affecting you. For example, if you have no symptoms you may not need any treatment for a while. In this case your haematologist will monitor your condition regularly. If you develop any symptoms in between appointments, let your specialist know.

If you have symptoms caused by a low red blood cell count (anaemia) you can be given transfusions of blood. Usually it is possible to have a blood transfusion as a day-patient, but it may involve an overnight stay in hospital. Blood transfusions can be repeated as often as necessary.

Chemotherapy Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy cancer cells. It may be used to treat myelofibrosis, especially if the symptoms are severe. Chemotherapy can help to reduce the size of the spleen and the liver, and can help to control other problems. It may also help to increase the number of blood cells. A number of different chemotherapy drugs can be used. Chemotherapy is often given to you as a day-patient but may involve you having to stay in hospital overnight.

One of the side effects of chemotherapy is to temporarily reduce the function of the bone marrow. For this reason, chemotherapy is not suitable for everyone with myelofibrosis and those that are treated need to be monitored very closely. Often the doses of chemotherapy are greatly reduced to help lower the risk of side effects.

Your doctor or nurse will explain which drugs you are to have and any possible side effects.

Splenectomy This is an operation to remove the spleen. If you have a very low number of platelets, your spleen is enlarged, contains many blood cells, and is causing pain and discomfort; your specialist may suggest a splenectomy to improve your symptoms. This can be a risky operation for someone with myelofibrosis and your specialist should discuss the pros and cons with you before you decide whether to go ahead or not.

Radiotherapy If it isn’t possible to remove the spleen, it may be possible to shrink an enlarged spleen using radiotherapy. Radiotherapy is the use of high energy x-rays. Radiotherapy to the spleen can help to improve symptoms such as pain and a high platelet count. Unfortunately the improvements in symptoms are temporary and may only last for a few months. Radiotherapy can cause side effects such as tiredness and skin irritation, although generally this is mild.

High-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell transplant A small number of younger people with myelofibrosis may be able to have high-dose chemotherapy followed by a stem-cell transplant usually from a donor (an allogeneic transplant). Stem cells are blood cells at their very earliest stage of development. It is possible to collect them from the blood of a donor and store them ready to be transfused back into the person with myelofibrosis. Usually the donor is a brother or sister. Before the stem cells are transplanted you will be given high doses of chemotherapy to destroy your bone marrow. Once stem cells are transplanted they start developing into mature blood cells that eventually replace the cells your bone marrow produced before transplant and before you got your blood disorder. A stem cell transplant involves a hospital stay for at least a couple of weeks.

There are risks associated with this procedure and as a result it is generally only suitable for people under 45 years. High-dose treatment with a stem-cell transplant is not always successful.

If suitable, your specialist will discuss the possible risks of this treatment to help you decide whether or not to have a transplant.

Clinical trials

Research into new ways of treating myelofibrosis is ongoing. Doctors use clinical trials to assess new treatments. The drug thalidomide is being investigated to determine if it is useful in the treatment of myelofibrosis. You may be asked to take part in this trial.

Thalidomide tablets may help to improve the number of red blood cells and platelets. Side effects can include: nausea, headaches, constipation, an increased risk of blood clots and numbness or tingling in the hands and feet.

Before any trial is allowed to take place, it must be approved by a research ethics committee, which protects the interests of those taking part. Before you enter a trial your doctor or research nurse must discuss the treatment with you so that you have a full understanding of the trial and what it means to take part. You may decide not to take part or to withdraw from the trial at any stage. You will then receive the best standard treatment available.

Follow-up

You will need to have regular check-ups and blood tests. These will probably be ongoing. If you have any problems, or notice any new symptoms in between these times, let your nurse or doctor know as soon as possible.

Your feelings and support

The need for practical and emotional support will of course be individual. Some people with myelofibrosis may find that their life is not affected very much, but for others the condition may be a source of great fear and distress.

You may have many different emotions including anger, resentment, guilt, anxiety and fear. These are all normal reactions and are part of the process many people go through in trying to come to terms with their condition and its treatment.

You don’t have to cope with these feelings on your own; people are available to help you. Some hospitals have their own emotional support services with specially trained staff, and some of the nurses will have received training in counselling. CancerBACUP can put you in contact with counselling services in your area.

References

This section has been compiled using information from a number of reliable sources including;

- Essential Haematology (4th edition) Hoffbrand et al. Blackwell Scientific Publications, 2001.

- Wintrobe’s Clinical Haematology (11th edition) R Lee et al. Williams and Wilkins, 2004.

Page last modified: 29 November 2005