Gastro intestinal stromal tumour (GIST)

What is a GIST?

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) belong to a group of cancers called soft tissue sarcomas.

Sarcomas are cancers that develop in the supporting or connective tissues of the body (such as muscle, fat, nerves, blood vessels, bone and cartilage).

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare. Approximately 1,200–2,000 people will be diagnosed with a sarcoma each year in the UK.

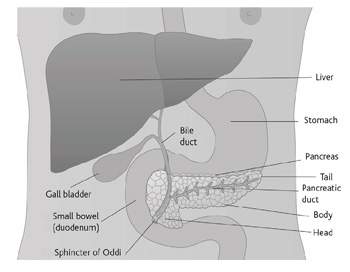

GISTs are a rare type of soft tissue sarcoma, so they are very rare indeed. About 60% of GISTs occur in the stomach, but they can occur anywhere along the length of the digestive system from the gullet (oesophagus) to the anus (back passage). They start in the cells of the stroma. The stroma is the connective tissue that supports the organs involved in digesting food. The digestive system is often called the gastrointestinal tract.

Causes

The exact causes of GISTs are unknown, and research is ongoing to try and find out as much as possible about this condition. However, scientists have discovered that most GIST cells have an enzyme disorder. An enzyme called tyrosine kinase is responsible for sending signals inside the cell, which stimulate the cell to grow and divide. The tyrosine kinase enzyme can trigger the growth of some GIST tumour cells.

Most people who have been diagnosed with GIST do not have a family history of the condition. However, there are very rare cases where several family members have been diagnosed with GIST. People with a condition called neurofibromatosis have a slightly increased risk of developing a GIST. GISTs rarely occur in people younger than 50.

Signs and symptoms

People with an early-stage GIST often do not have any symptoms of the disease. Most GISTs are diagnosed after a person develops symptoms. These may include:

- a painless lump in the abdomen

- abdominal discomfort or pain

- vomiting (being sick)

- blood in the stools (bowel motions) or vomit

- fatigue (tiredness and a feeling of weakness)

- a high temperature (fever) and sweating at night

- anaemia (a low level of iron in the blood).

If you notice any of the above, contact your GP, but remember that these symptoms can also be caused by other conditions.

How GISTs are diagnosed

Usually you begin by seeing your family doctor (GP) who will examine you and refer you to a hospital specialist.

The hospital specialist will organise any tests that may be necessary and can give you expert advice and treatment. The doctor will take your full medical history, do a physical examination and take blood samples to check your general health. The following tests may be carried out:

Endoscopy This is the most common test used to diagnose any problems in the stomach and oesophagus (gullet). Before an endoscopy, the stomach has to be empty, so you will be asked not to eat or drink anything for at least four hours beforehand. Once you are lying comfortably on the couch you will be given a sedative, usually into a vein in your arm. This will make you feel sleepy and reduce any discomfort during the test. A local anaesthetic is then sprayed onto the back of your throat and the doctor passes an endoscope, (a flexible telescope) down the gullet into the stomach. Photographs are taken of the stomach, and a small sample of cells (biopsy) can be taken, for examination under a microscope.

Sometimes the endoscopy tube has an ultrasound probe at the end, which allows an ultrasound scan to be done of the stomach and surrounding structures. This is known as endoscopic ultrasound.

An endoscopy can be uncomfortable but it is not painful. After a few hours the effects of the sedative should have worn off and you will be able to go home. You should not drive for several hours afterwards. It is a good idea to arrange for someone to travel home with you. Some people have a sore throat after their endoscopy. This is normal and should disappear after a couple of days.

Ultrasound scan Sound waves are used to make up a picture of the abdomen and surrounding organs. The scan is done in the hospital scanning department. You will be asked not to eat, and to drink clear fluids only (nothing fizzy or milky) for 4–6 hours before the scan. Once you are lying comfortably on your back, a gel is spread onto your abdomen. A small device like a microphone is then rubbed over the area. The sound waves are converted into a picture using a computer. The test is completely painless and takes about 15–20 minutes.

CT (computerised tomography) scan A CT scan takes a series of x-rays that are fed into a computer to build up a detailed picture of the stomach. On the day of the scan you will be asked not to eat or drink anything for at least four hours before your appointment. You will be given a special liquid to drink an hour before the test and again immediately before the scan. The liquid shows up on x-ray to ensure that clear pictures can be taken.

Once you are in a comfortable position the scan can be taken. The scan itself is painless but it will mean lying still for about 10–30 minutes.

Most people are able to go home as soon as their scan is over.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan This test is similar to a CT scan, but uses magnetism instead of x-rays to build up cross-sectional pictures of your body. During the test you will be asked to lie very still on a couch inside a large metal cylinder that is open at both ends. The whole test may take up to an hour. It can be slightly uncomfortable and some people feel a bit claustrophobic during the scan. It is very noisy. You will be given earplugs or headphones to wear. You can usually take someone with you into the room to keep you company. A two-way intercom allows you to talk with the people controlling the scanner. If you have any metal implants (such as surgical clips, pacemakers, metal in the eye from previous accidents or trauma) it will not be possible for you to have this test.

Biopsy The results of the previous tests may make your doctor strongly suspect a diagnosis of cancer. However, the only way to be sure it is a cancer is to take some cells or a small piece of tissue from the affected area to look at under a microscope. This is called a biopsy. To take the biopsy, the skin over the stomach is numbed using a local anaesthetic injection. A fine needle is then passed into the tumour through the skin. CT or ultrasound scanning may be used at the same time, to make sure that the biopsy is taken from the right place.

When the cells are looked at under a microscope, the pathologist will be able to tell whether they are benign (not cancerous) or cancerous (malignant). If a sarcoma is diagnosed, further tests may be done on the sample to try to find out exactly what type of sarcoma it is. One of the things the pathologist will look for when diagnosing a GIST is whether there are detectable amounts of the tyrosine kinase protein. The protein can be detected using an antibody called the CD117 antigen. If high levels of tyrosine kinase are present this helps to identify the tumour as a GIST.

Staging and grading

Staging

The stage of a cancer is a term used to describe its size and whether it has spread beyond its original site. Knowing the particular type and the stage of the cancer helps the doctors to decide on the most appropriate treatment.

Generally, sarcomas are divided into four stages, from ‘small and localised’ (stage one) to ‘spread into surrounding structures’ (stages two or three) or ‘spread to other parts of the body’ (stage four). If the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body this is known as secondary or metastatic cancer.

As GISTs are very rare there is no established staging system.

Recurrence means that a soft tissue sarcoma has come back after it was first treated. It may come back in the tissues where it first started (local recurrence) or it may come back in another part of the body (metastasis).

Grading

Grading refers to the appearance of the cancer cells under the microscope. The grade gives an idea of how quickly the cancer may develop. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas can sometimes be difficult, especially for the less common types. Low-grade means that the cancer cells look very like the normal cells of the soft tissues. They are usually slow-growing and are less likely to spread. In high-grade tumours the cells look very abnormal. They are likely to grow more quickly and are more likely to spread.

Treatment

The treatment for GIST depends on a number of things, including your general health and the size and position of the tumour. The results of your tests will enable your doctor to discuss with you the best treatment for your situation.

The most common treatment is surgery to remove the tumour. As there is a chance that GISTs can come back (recur) after surgery, other treatments such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatments may also be given. This is called adjuvant therapy. However, in the case of GIST, using chemotherapy or radiotherapy after surgery has not been very effective in preventing the tumour from coming back.

A newer type of drug known as imatinib (pronounced i mat i nib; also known as Glivec®) has recently been shown to be effective in treating GISTs. Imatinib is a type of drug called a tyrosine kinase inhibitor. It blocks the tyrosine kinase enzyme that the cancer needs in order to grow.

It is only used if the GIST:

- cannot be removed by surgery alone

- has spread

- has come back since it was first treated

Surgery is still the best treatment for curing GIST. If your GIST cannot be removed by surgery, your specialist might prescribe Glivec® to try and shrink it so that it can be removed surgically.

If you had part or most of your stomach removed you may have some difficulties with eating afterwards.

Clinical trials

Research into treatments for GIST is continuing and advances are being made. Cancer doctors use clinical trials to assess new treatments.

You may be asked to take part in a clinical trial. Your doctor must discuss the treatment with you so that you have a full understanding of the trial and what it means to take part. You may decide not to take part or to withdraw from a trial at any stage. You will then receive the best standard treatment available.

Your feelings

Having a cancer diagnosis can be extremely frightening. You may have many different emotions, including anger, resentment, guilt, anxiety and fear. These are all normal reactions and are part of the process that many people go through in trying to come to terms with thir condition. Many people find it helpful to talk things over with their doctor or specialist nurse. Close family members and friends can also offer support. You may also find our section on the emotional effects of cancer helpful.

References

This section has been compiled using information from a number of reliable sources including;

- Textbook of Uncommon Cancers (2nd edition). Raghavan et al. Wiley, 1999.

- Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors (4th edition). Weiss et al. Mosby, 2001.

For further references, please see the general bibliography.

Page last modified: 02 November 2005