Primary liver cancer

Cancerous (malignant) tumours of the liver can be:

- primary cancer cancer starting in the liver itself. This is discussed in this section

- secondary or metastatic cancer cancer which started in another part of the body and has spread to the liver. This is discussed in CancerBACUP’s section on secondary cancer in the liver.

The liver

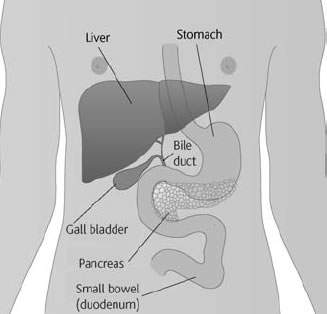

The liver is the largest organ in the body, and the main heat-producing organ. It is surrounded by a fibrous capsule and is divided into sections called lobes. It is situated in the upper part of the abdomen on the right-hand side of the body and is surrounded and protected from injury by the lower ribs.

The liver is an extremely important organ that has many functions. This includes producing proteins that circulate in the blood. Some of these help the blood to clot and prevent excessive bleeding, while others are essential for maintaining the balance of fluid in the body.

The liver also destroys harmful substances such as alcohol, and gets rid of waste products. It does this by breaking down substances not used by the body so that they can be passed out in the urine or stools (bowel motions).

The liver is also responsible for breaking down food containing carbohydrates (sugars) and fats, so that they can be used by the body for energy. It stores substances such as glucose and vitamins so that they can be used by the body when needed. The liver also produces bile, a substance which breaks down the fats in food so that they can be absorbed from the bowel (intestine).

The liver is connected to the small intestine (duodenum) by a tube called the bile duct. This duct takes the bile produced by the liver to the intestine.

The liver has an amazing ability to repair itself. It can function normally with only a small part of it in working order.

Primary liver cancer

Primary liver cancer is quite rare in the UK and the rest of the western world, but the number of people developing it is increasing. Approximately 1500 people are diagnosed with this type of cancer each year in the UK. In other parts of the world, such as tropical Africa and some parts of Asia, it is one of the most common cancers. It is twice as common in men as in women.

There are two different types of primary liver cancer. The most common kind is called hepatoma or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and arises from the main cells of the liver (the hepatocytes). This type is usually confined to the liver, although occasionally it spreads to other organs. It occurs mostly in people with a liver disease called cirrhosis (see Causes, below). There is also a rarer sub-type of hepatoma called Fibrolamellar hepatoma, which may occur in younger people and is not related to previous liver disease.

The other type of primary liver cancer is called cholangiocarcinoma or bile duct cancer, because it starts in the cells lining the bile ducts.

Some primary tumours in the liver are non-cancerous (benign) and do not spread to other parts of the body. They are usually small and may cause no symptoms, and are often discovered by chance during operations or investigations for other conditions. Unless they are causing symptoms they do not usually need to be removed.

What causes primary liver cancer?

In the western world, most people who develop hepatoma usually also have a condition called cirrhosis of the liver. This is a fine scarring throughout the liver which is due to a variety of causes including infection and heavy alcohol drinking over a long period of time. However, only a small proportion of people who have cirrhosis of the liver develop primary liver cancer.

Infection with either the hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus can lead to liver cancer, and can also be the cause of cirrhosis, which increases the risk of developing hepatoma.

People who have a rare condition called haemochromatosis, which causes excess deposits of iron in the body, have a higher chance of developing hepatoma.

In Africa and Asia a poison called aflatoxin, found in mouldy peanuts and grain, is an important cause of hepatoma.

Bile duct cancers (cholangiocarcinomas) are less common than hepatomas. The cause of most bile duct cancers is unknown, but they are slightly more likely to occur in people with conditions which cause inflammation of the bowel, such as ulcerative colitis. In Africa and Asia, infection with a parasite known as the liver fluke is thought to cause many cholangiocarcinomas.

In the western world, cancer of the liver usually occurs in middle-aged and elderly people, although rarely it can also affect children and young adults. In Africa and Asia it often occurs in young adults.

What are the symptoms?

In the early stages of primary liver cancer there are often no symptoms.

People sometimes notice a vague discomfort in the upper abdomen that may become painful. This is due to enlargement of the liver. Pain can sometimes also be felt in the right shoulder. This is known as referred pain and is due to an enlarged liver stimulating the nerves beneath the diaphragm (the sheet of muscle under the lungs) which are connected to nerves in the right shoulder.

Loss of appetite, weight loss, feeling sick (nausea), and weakness and tiredness (lethargy) are common symptoms. Some people may also develop a high temperature and feel shivery.

Jaundice If the bile duct becomes blocked, bile produced by the liver will flow back into the bloodstream, causing jaundice. This will cause the skin and whites of the eyes to go yellow and may make the skin very itchy. The itching may sometimes be relieved by antihistamine tablets or other drugs, which your doctor can prescribe. Sometimes the jaundice itself can be relieved. This is done by inserting a narrow tube called a stent into the bile duct to keep it open and to allow the bile to flow normally into the small intestine.

Other signs of jaundice are dark-coloured urine and pale stools (bowel motions).

Ascites Sometimes fluid builds up in the abdomen and causes swelling known as ascites. There may be several possible reasons for this:

- if cancer cells have spread to the lining of the abdomen, they can irritate it and cause fluid to build up

- if the liver itself is affected by cancer cells, this causes an increase in pressure in the veins that lead into the liver. Fluid from the abdomen cannot then pass quickly enough through the liver, so it starts to collect in the abdomen

- if the liver is damaged, it may produce less blood protein. This may upset the body’s fluid balance, which causes fluid to build up in the body tissues, including the abdomen

- cancer cells blocking the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is a network of fine channels which runs throughout the body. One of its functions is to drain off excess fluid, which is eventually passed out of the body in the urine. If some of these channels are blocked, the system cannot drain efficiently and fluid may build up.

If ascites does develop, a tube can be put through the wall of the abdomen to drain the fluid away.

How is it diagnosed?

Usually you begin by seeing your family doctor (GP), who will examine you and arrange for any tests or x-rays that may be necessary. Your GP will refer you to a hospital specialist for these tests and for expert advice and treatment.

- You will have a physical examination and a blood test.

- Your doctor may arrange for you to have one or more of the following tests: a liver ultrasound scan, an abdominal CT (computerised tomography) scan, an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan, a test to outline the blood supply in the liver (hepatic arteriography) or a liver biopsy.

Staging

The ‘stage’ of a cancer is a term used to describe its size and whether it has spread beyond its original site. Knowing the particular type and the stage of the cancer helps the doctors to decide on the most appropriate treatment.

Cancer can spread in the body, either in the bloodstream or through the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is part of the body’s defence against infection and disease. The system is made up of a network of lymph glands (also known as lymph nodes) that are linked by fine ducts containing lymph fluid. Your doctors will usually check the lymph nodes close to the liver to help find the stage of your cancer.

Stage 1 The cancer is no bigger than 2cm in size, and has not begun to spread.

Stage 2 The cancer is affecting blood vessels in the liver, or there is more than one tumour in the liver.

Stage 3A The cancer is bigger than 5cm in size or has spread to the blood vessels near the liver.

Stage 3B The cancer has spread to nearby organs, such as the bowel or the stomach, but has not spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage 3C The cancer can be of any size and has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 4 The cancer has spread to parts of the body further away from the liver, such as the lungs.

If the cancer comes back after initial treatment this is known as recurrent cancer.

Treatment

Your doctor will plan your treatment taking into account a number of factors:

- whether the cancer is a primary or secondary liver cancer

- your age

- your general health

- the type and size of the cancer

- whether it has spread beyond the liver

- whether the liver is affected by any other disease, such as cirrhosis

If you have any questions about your own treatment, don’t be afraid to ask your doctor or the nurse who is looking after you. It often helps to make a list of questions for your doctor and to take a close friend or relative with you.

Some people find it reassuring to have another medical opinion to help them decide about their treatment. Most doctors will be pleased to refer you to another specialist for a second opinion if you feel this will be helpful.

Surgery

Surgery is the most effective treatment for primary liver cancer, but this is not always possible due to the size or position of the tumour. It is also not possible to operate if the cancer has spread beyond the liver.

If only certain areas of the liver are affected by the cancer and the rest of the liver is healthy, it may be possible to have an operation to remove the affected part: this is called a liver resection. If the operation removes a whole lobe of the liver, it is called a lobectomy. If the liver is severely damaged by cirrhosis it may not be safe to have surgery.

The liver has an amazing ability to repair itself. Even if up to three-quarters of the liver is removed it will start to re-grow very quickly, and may be back to normal size within a few weeks.

Removing the whole liver and replacing it with a liver from another person (a liver transplant) is another possible form of treatment for primary liver cancer, but can only be done in a very few cases when the tumour is small.

Before any operation, it is important to discuss it fully with your doctor so that you understand what it involves.

After your operation The hospital staff will tell you what to expect after the operation. You may be taken to the intensive care ward until you have fully recovered from the anaesthetic (this usually takes about 24 hours).

It is normal to have some pain or discomfort after an operation on the liver. You will be given regular injections of painkillers for several days after the operation to prevent and relieve pain. Most people are able to go home 6–12 days after their operation and will need painkillers for the next few weeks. It may take up to 6 weeks before you start getting back to

normal.

Tumour ablation

This type of treatment is used for tumours less than 5cm in diameter. Liquids such as alcohol (ethanol) or acetic acid are injected through the skin and into the tumour. The liquids destroy the cancer cells. This procedure is usually done in the scanning department so that ultrasound can be used to guide the needle directly into the tumour. If the tumour grows again, the treatment can be repeated.

Laser or radiofrequency (thermal) ablation

This treatment uses a laser or electrical generator to destroy the cancer cells. Under local anaesthetic, a fine needle is inserted into the centre of the tumour. Powerful laser light or radio waves are then passed through the needle and into the tumour; these heat the cancer cells and destroy them.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy cancer cells. It is sometimes used to treat primary liver cancers that cannot be removed.

Chemotherapy drugs are usually given by injection into a vein (intravenously) or by injecting the drug directly into the hepatic artery (the blood vessel that takes blood to the liver).

Chemotherapy is often given as a session of treatment, usually lasting a few days. This is followed by a rest period of a few weeks to allow your body to recover from any side effects of the treatment. The number of sessions you have will depend on the type of liver cancer you have and how well it is responding to the drugs.

Side effects of chemotherapy Chemotherapy can sometimes cause unpleasant side effects, but it can also make you feel better by relieving the symptoms of the cancer. Any side effects that do occur are usually temporary and can often be well controlled with medicine. The main side effects are a reduced resistance to infection, feeling sick, a sore mouth, and hair loss.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is the use of high-energy rays to destroy cancer cells, while doing as little harm as possible to normal cells. It is not usually used to treat hepatomas, but it may be used to treat cholangiocarcinoma.

Other treatments

The following treatments are still being evaluated as part of research trials. Your cancer specialist will be able to discuss with you whether they may be helpful in your situation, and can refer you to a hospital which carries out these treatments.

Cryosurgery or cryotherapy In cryotherapy treatment a device called a cryoprobe is inserted into the centre of the tumour during an operation. Liquid nitrogen is then passed through the probe. This freezes the surrounding area and destroys the cancer cells.

Chemoembolisation This treatment involves mixing chemotherapy drugs with an oily substance called lipiodol. Under local anaesthetic the mixture is then injected into the liver through a tube inserted into the hepatic artery (the main blood vessel carrying blood to the liver). It is thought that adding lipiodol to the chemotherapy drugs helps them to remain in the liver for longer, and makes the treatment more effective. This treatment can be repeated several times. It is carried out in the x-ray department and usually needs a stay in hospital of 24–48 hours.

Follow-up

After your treatment has been completed, your doctor will ask you to return for regular check-ups and x-rays or scans. These are good opportunities to discuss with your doctor any worries or problems you may have. However, if you notice any new symptoms or are anxious about anything else in the meantime, contact your doctor or the ward sister for advice.

For people whose treatment is over apart from regular check-ups, CancerBACUP’s section on adjusting to life after cancer treatment gives useful advice on how to keep healthy and adjust to normal life.

Clinical trials

Research into treatments for primary liver cancer is ongoing and advances are being made. Cancer doctors use clinical trials to assess new treatments.

You may be asked to take part in a clinical trial. Your doctor must discuss the treatment with you so that you have a full understanding of the trial and what it means to take part.

CancerBACUP has a section that explains how clinical trials are set up and answers common questions that people have about them.

Your feelings

During your diagnosis and treatment you are likely to experience a number of different emotions, from shock and disbelief to fear and anger. At times these emotions can be overwhelming and hard to control. It is quite natural, and important, to be able to express them. Everyone has their own ways of coping with difficult situations; some people find it helpful to talk to friends or family, while others prefer to seek help from people outside their situation. Others prefer to keep their feelings to themselves. There is no right or wrong way to cope, but help is available if you need it.

If you would like to talk to someone about your situation or how you are feeling, please contact CancerBACUP’s Cancer Support Service. Specialist nurses can talk through any concerns you may have and suggest other sources of support.

References

This section has been compiled using information from a number of reliable sources including;

- Oxford Textbook of Oncology (2nd edition). Souhami et al. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Gastrointestinal Oncology: Principles and Practice. Kelsen et al. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2002.

- The Textbook of Uncommon Cancers (2nd edition). Raghavan et al. Wiley, 1999.

- Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. NICE July 2003.

For further references, please see the general bibliography.

Page last modified: 02 November 2005

- Q&As

- Related information

- Current clinical trials