Cancer of the nasopharynx (nasopharyngeal cancer)

This information is about cancer of the nasopharynx (nasopharyngeal cancer). You may find it helpful to read the information alongside CancerBACUP’s general information about head and neck cancers, which discusses the treatments and their effects in more detail.

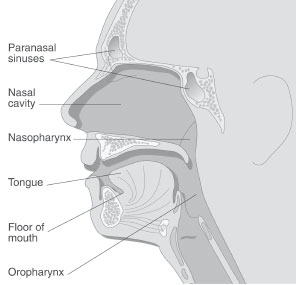

The nasopharynx

The nasopharynx is an airspace lying at the back of the nose and above the soft part of the palate (roof of the mouth). It connects the nose to the back of the mouth (oropharynx), allowing you to breathe through your nose and to swallow mucus produced by the lining membranes of the nose.

Cancer of the nasopharynx

This type of cancer is rare in the West, but much more common in countries of the Far East. Approximately 230 new cases of nasopharyngeal cancer are diagnosed each year in the UK. It can occur at any age, but is more likely to be seen in people aged between 50 and 60. It affects more men than women.

Causes

The exact cause of cancer of the nasopharynx is unknown. In some areas of the world, such as China and North Africa, dietary factors (such as the cooking of salt-cured fish and meat, which releases chemicals known as nitrosamines) are thought to increase a person’s risk of developing the disease. The Epstein-Barr virus has also been linked to an increased risk of developing nasopharyngeal cancer. As with other cancers, nasopharyngeal cancer is not infectious and cannot be passed on to other people.

Signs and symptoms

One of the first symptoms is often a painless swelling or lump in the upper neck. Other symptoms may include any of the following:

- a blocked nose

- nosebleeds

- changes in hearing

- tinnitus (ringing in the ears).

These symptoms are common in conditions other than cancer and most people with these symptoms will not have cancer of the nasopharynx. However, like most cancers, nasopharyngeal cancer is best treated when diagnosed at an early stage, therefore any of the above symptoms that do not improve after a few days should be reported to your family doctor (GP).

How it is diagnosed

Your GP will examine your mouth, throat and ears. They will refer you to a hospital for any further tests and for specialist advice and treatment.

The specialist will examine your nasopharynx by using a small mirror and light. A very thin flexible tube with a light at the end (nasendoscope) will be passed into the nostril in order to get a better view of the back of the nose. This can be uncomfortable and you may be given a local anaesthetic spray to numb your nose and throat. If you do have a local anaesthetic to your throat you may be instructed not to eat or drink anything for about an hour afterwards until your throat has lost the numb feeling.

In order to make a diagnosis, a piece of tissue will be removed and then examined under a microscope. This procedure, known as a biopsy, is performed under a general anaesthetic, and you may need to spend the night in hospital.

Further tests

You may have a blood test and a chest x-ray to check your general health. There are several other tests which may be used to help diagnose cancer of the nasopharynx, and to check whether the cancer has spread. Cancer can spread in the body, either in the bloodstream or through the lymphatic system.

The lymphatic system is part of the body’s defence against infection and disease. The system is made up of a network of lymph glands or nodes that are linked by fine ducts containing lymph fluid. The results of these tests will help the specialist to decide on the best type of treatment for you.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan

This uses magnetic fields to form a series of cross-sectional pictures of the inside of the body. During the scan you will be asked to lie very still on a couch inside a metal cylinder. You may be given an injection to allow the pictures to be seen more clearly. The test can take up to an hour and is completely painless. The machine is quite noisy but you will be given earplugs or headphones to wear. If you do not like enclosed spaces you may find the machine claustrophobic. It often helps to have a friend in the room with you for company.

Before entering the scanning room you will be asked to remove anything metal such as jewellery, as this may affect the scanning machine. If you have had any operations to insert metal objects into your body (such as a hip replacement or a pacemaker) it is important to tell the person doing the scan before you go into the scanning room.

CT (computerised tomography) scan

This is a sophisticated type of x-ray which builds up a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body. The scan is painless but takes longer than an x-ray (10–15 minutes). It may be used to identify the exact site of the tumour or to check for any spread of the cancer. Most people who have a CT scan are given a drink or injection to allow particular areas to be seen more clearly. Before having the injection or drink, it is important to tell the person doing this test if you are allergic to iodine or have asthma.

Isotope bone scan

This is a test which shows up any abnormal areas of bone. A very small amount of a mildly radioactive substance is injected into a vein, usually in the arm. Two to three hours later, a scan is taken of the whole body. As abnormal bone absorbs more of the radioactive substance than normal bone, any abnormal areas show up on the scan as highlighted areas (sometimes known as ‘hot spots’).

This scan will not make you radioactive and it is perfectly safe for you to be with other people afterwards.

Staging

The stage of a cancer is a term used to describe its size and whether it has spread beyond its original site. Knowing the particular type and the stage of the cancer helps the doctors to decide on the most appropriate treatment.

- Stage 1 The cancer is found in the nasopharynx only.

- Stage 2 The cancer has spread to the oropharynx, the nasal cavity or the lymph nodes on one side of the neck.

- Stage 3 The cancer has spread to either the lymph nodes on both side of the neck, or to the sinuses or nearby bones.

- Stage 4 The cancer has spread to other parts of the head, or to other parts of the body.

Grading

Grading refers to the appearance of the cancer cells under the microscope and gives an idea of how quickly the cancer may develop. Low-grade means that the cancer cells look very like normal cells; they are usually slow-growing and are less likely to spread. In high-grade tumours the cells look very abnormal, are likely to grow more quickly and are more likely to spread.

Treatment

The treatment you will have depends on the type and stage of the nasopharyngeal cancer.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is the main treatment for nasopharyngeal cancer. Radiotherapy treats cancer by using high-energy rays to destroy cancer cells, whilst doing as little harm as possible to normal tissue. The radiotherapy is usually given to the lymph glands in the neck as well as the nasopharyngeal area.

The types of radiotherapy used to treat cancer of the nasopharynx are external radiotherapy (from a radiotherapy machine) and occasionally internal radiotherapy (placing radioactive metal close to the tumour). External radiotherapy is the main type used; however, some people may go on to have internal radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy to the nasopharynx can cause the salivary glands to produce less saliva and it is important to keep your mouth clean. Your doctors and nurses will advise you how to do this.

If you have a dry mouth it is important to see a dentist regularly. It is best not to have teeth taken out after radiotherapy to this area, but if it is necessary to have a tooth removed this should be done by a hospital specialist.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be given before, alongside, or after radiotherapy.

Research trials You may be offered chemotherapy as part of a research trial. Before any trial is allowed to take place, it must have been approved by the ethics committee, which checks that the trial is in the interest of patients. Your doctor must discuss this treatment with you so that you have a full understanding of the trial and what it means to take part. You may decide not to take part or withdraw from a trial at any stage.

Surgery

Occasionally the doctor may recommend surgery to remove any affected lymph nodes in the neck that may still contain cancer cells after the radiotherapy treatment. There is a network of lymph nodes (or glands) throughout the body which form part of the body’s natural defence against infection. The lymph nodes are connected by a network of tiny tubes known as lymph vessels.

Surgery may also be used to remove the tumour if it comes back.

Follow-up

After your treatment is completed, you will have regular check-ups and possibly scans or x-rays. These will probably continue for several years. If you have any problems, or notice any new symptoms between these times, let your doctor know as soon as possible.

For people whose treatment is over apart from regular check-ups, CancerBACUP’s section on adjusting to life after cancer treatment gives useful advice on how to keep healthy and adjust to life after cancer.

Your feelings

You are likely to experience a number of different emotions, from shock and disbelief to fear and anger. These feelings may be overwhelming and difficult to control, particularly if you have experienced changes in your appearance and feel self-conscious. These feelings are quite natural and it is important for you to be able to express them.

Everyone has their own ways of coping with difficult situations; some people find it helpful to talk to friends or family, while others prefer to seek help from people outside their situation. Others prefer to keep their feelings to themselves. There is no right or wrong way to cope; but help is there if you need it. You may wish to contact our Cancer Support Service for information about counselling in your area.

CancerBACUP also has a section on the emotional effects of cancer, which has advice on coping with the emotions that may occur.

References

This section has been compiled using information from a number of reliable sources including;

- Oxford Textbook of Oncology (2nd edition). Souhami et al. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Cancer and its Management (4th edition). Souhami and Tobias. Oxford Blackwell Scientific Publications, 2003.

- The Textbook of Uncommon Cancers (2nd edition). Raghavan et al. Wiley, 1999.

- Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology (7th edition). DeVita et al. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2005.

For further references, please see the general bibliography.

Page last modified: 02 November 2005

- Q&As

- Related information